Here are a couple of observations on the nature of writing for performance.

MOZART:

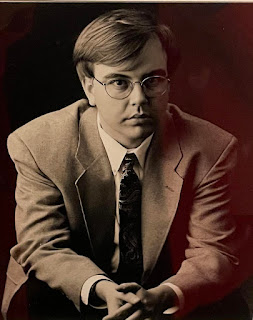

Some years ago, I found myself taking a summer course in playwriting from noted playwright Allen Partridge. I was toiling away on what was to become Diving In. We students would turn in our pages each day, and receive his teacherly criticism the next day.

One day, Partridge handed back my pages and he had written in red ink on the top page "Too many notes, Wolfgang!" It was the only note. I queried him and he responded "Watch Amadeus." So I did. Near the beginning of the film, Emperor Joseph II give Mozart some helpful advice:

"My dear young man, don't take it too hard. Your work is ingenious. It's quality work. And there are simply too many notes, that's all. Just cut a few and it will be perfect."So I took this up with Partridge, and received the best piece of writing advice I've ever been given. Essentially, why use a paragraph when a well wrought phrase would accomplish the same thing? Economy of word leads to greater emotional impact.

The analogy is a bit off, because one should strive to write like Mozart. In Mozart's work, every note is in its proper place. There is nothing superfluous. Or as Mozart retorts to the Emporer:

"Which few did you have in mind, Majesty?"Of course, he was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and I was just a snot-nosed young playwright. Indeed, Diving In had a few too many "notes." It's a lesson I'm still learning.

BEETHOVEN:

The way I learned it, when Beethoven went deaf, his music went nuts. Musicians complained about the difficulty of performing his music. The notes were too high, too difficult to reach; his passages were far too complex to play with human hands. And yet, the music is beautiful, challenging and nuanced.

Well, I try to write like Beethoven.

Oh, I don't get too ridiculous with the demands I put on a performer. I don't expect them to sprout wings or bleed tapioca pudding.

However, I may write a character who makes an emotional turn "on a dime." I have a certain fondness for repetition in monologues that makes them difficult to memorize. I may even force a performer to say words and relate experiences that are horrible, embarrassing, disgusting, etc. It's only because I respect actors enough to bring my "A" game as a writer.

Mamet does this. Read Oleanna sometime. It's perhaps the most infuriating piece of dramatic literature that I've ever thrown across the room (several times.) The more I read it, the more I grow to appreciate it. It's compelling, subtle, nuanced. It's also two actors with their asses glued to furniture blathering on and on in a repetitious verbal tennis match. On the surface, nothing really seems to happen. I had the good fortune to direct the final scene of the play for an acting class, and I really began to get it: The slow burn, the psychological chess match.

I do try to write like Beethoven and write like Mozart. Because if I'm not going to really put forth the effort, what's the damn point?

No comments:

Post a Comment